India’s construction of barrages and water diversion structures along the Teesta and Mahananda rivers creates a significant transboundary water crisis for Bangladesh.

This image (Figure 1) shows the Teesta Barrage at Gajoldoba, West Bengal, India. It highlights two major water diversion structures (east and west) on either side of the barrage. Water is being diverted from the Teesta River towards canals that lead to different regions in India, particularly the Dakshin Hanskhali area on the east and the Teesta-Mahananda Link Canal on the west. A smaller portion of water continues to flow downstream towards Bangladesh, which is already significantly reduced.

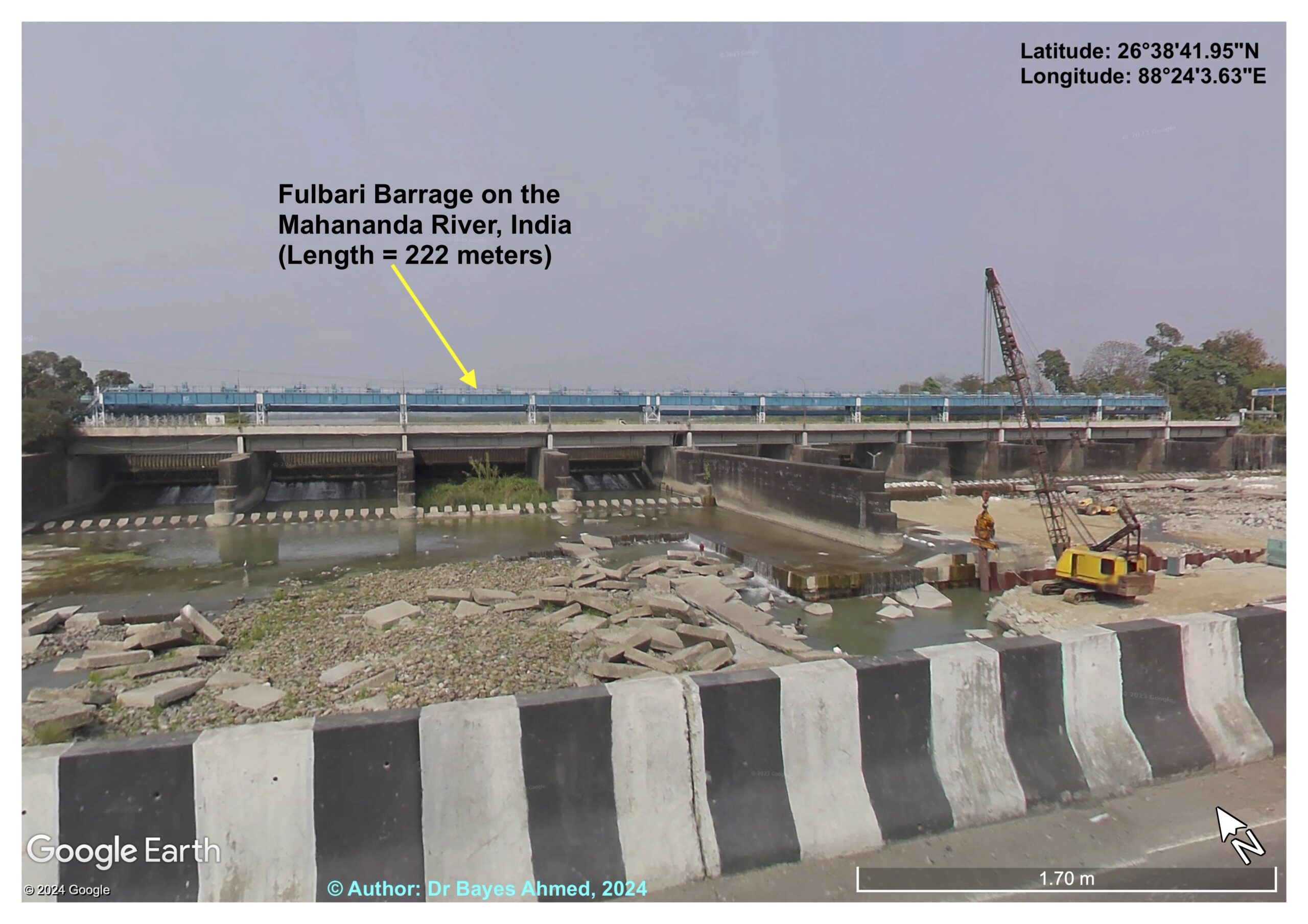

Figure 2 shows the path of the Teesta Mahananda Link Canal, a canal stretching 26.7 kilometres from the Teesta Barrage to the Fulbari Barrage (Latitude: 26°38’41.95″N and Longitude: 88°24’3.63″E) on the Mahananda River. The diversion canal is meant to redirect water from the Teesta River into the Mahananda River for use in India, effectively limiting the natural flow into Bangladesh.

This image focuses on the Fulbari Barrage on the Mahananda River, located just 1.55 kilometres away from the Bangladesh border. Water from the Teesta River is being funnelled into the Mahananda River through the Teesta Mahananda Link Canal. This diversion reduces the water flowing into Bangladesh from the Teesta and Mahananda rivers. The image also shows water being diverted westward towards other regions of India.

A close-up image of the Fulbari Barrage reveals more details about the inlet water diversion structure, which channels water from the Mahananda River towards the Dahuk River in India. Water flowing towards Bangladesh is marked as being just 1.5 kilometres away from the barrage. This proximity demonstrates how close the barrage is to Bangladesh’s border, affecting the country’s water security.

Summary: The images and water management practices depicted reveal a clear case of environmental injustice and hydrological domination. Bangladesh suffers from severe water shortages due to the diversion of transboundary rivers, leading to ecological degradation, livelihood destruction, artificial flooding, and economic instability. To address these issues, it is crucial for India and Bangladesh to establish more equitable water-sharing agreements, backed by the UN Convention on the Law of the Non-navigational Uses of International Watercourses, and transparent and cooperative management practices. Without such measures, the water crisis in Bangladesh will continue to intensify, threatening the livelihoods of millions of people in the region.